SIERRA DEL CRISTAL AND ALTURAS DE MOA ITS OPHIOLITIC RAINFORESTS SYNTAXA

Orlando J. Reyes 1, Félix Acosta Cantillo 2, Pedro Bergues Garrido 3.

1Centro Oriental de Ecosistemas y Biodiversidad (BIOECO). Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente (CITMA). José A. Saco Nr. 601, esq. Barnada. CP 90 100. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. joel@bioeco.cu

ABSTRACT

In order to know the rainforest characteristics developed over Sierra de Cristal and northeastern part of Moaˈs highlands the objective was to study these phytocoenosis by using Braun Blanquet method. One alliance and two associations are descripted for the first time, as soon as physiognomical, ecological and phytosociological characteristics are described which is too important for analyze the latter use of their community property.

Keywords: Rainforests, phytosociology, Sagua-Baracoa.

Recibido: 26 de mayo de 2021. Aceptado: 20 de julio de 2021

Received: May 26, 2021. Accepted: July 20, 2021

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33571/rpolitec.v17n34a12

SIERRA DEL CRISTAL Y ALTURAS DE MOA, SUS FITOCENOSIS EN LAS PLUVISILVAS SUBMONTANAS SOBRE OFIOLITAS

RESUMEN

Con vistas a conocer las características de las pluvisilvas sobre ofiolitas en la Sierra del Cristal y en la parte noroeste de las Alturas de Moa, el objetivo del trabajo fue estudiar las fitocenosis mediante el método de Braun Blanquet. Se describen por primera vez una alianza y dos asociaciones, así como sus condiciones fisionómicas, ecológicas y fitosociológicas, lo que tiene gran impacto para analizar el posterior uso de sus propiedades comunitarias.

Palabras clave: Pluvisilvas, fitosociología, Sagua-Baracoa.

How to cited the articule: O.J. Reyes, F. Acosta Cantillo and P. Bergues Garrido. “Sierra del Cristal and Alturas de Moa its ophiolitic rainforests syntaxa”. Revista Politécnica, vol. 17, no. 34, pp. 181-195. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33571/rpolitec.v17n34a12

1. INTRODUCTION

The rainforest has a wide distribution in tropical belts in planet even in Greater Antilles [4, 5, 6]. In Cuban Archipielago, where over this kind of forest important aspects are also described: protection [7, 8], ecological functioning [9, 10], lichens content [11, 12, 13] , ferns and similar plants [14],hepatics and mossy [15, 16], fungus [17] and plants with flowers [18, 19]. Rainforest is fundamentally distributed in Eastern Cuba where the biggest extensions and superior diversity is developed as structural as floristic [20, 21, 22, 23] as phytocenotic [20, 24, 25, 26], in Central Cuba Mountains only existing small pieces of mountain rainforest.

The geographic area [27] where this rainforest developed is one of the more ancient in Cuba, part of which remain emerged continuosly since Superior Cretaceus half [28]. Therefore are shelters of the original mountain serpentinitic flora of Cuba [20, 26, 29]. Nevertheless, the low and submontane rainforest on ophiolites (sclerophyll rainforest) restricted in Sagua-Baracoa Subregion [27], were found in areas where the level of rainfalls are the heighest in Cuban archipielago [30], it has been less study from the phytocenological point of view [20, 31], and for that the objective was to study these phytocoenoses and its characteristics to be able to know subsequently the propositions for it conservation and sustainable use.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Characteristics of study area

Low and submontane rainforest on ophiolites have their maximum expression at Sierra del Cristal area and Moa’s altitudes. The highest points of these territories are Pico Cristal Peak with 1 231 m osl and El Toldo Peak by 1 175 m osl at Moa’s Mountain. Rocks are ophiolites and the developed soils are dark red ferritic.

Air average temperature on highest areas is between 20 to 220C and in lowest 24 to 260C, only in El Toldo Peak and Cristal Peak the variability is between 12 to 200C [32]. Inside territories rain in Cristal Mountain range and Moa’s mountain is for about 2 000 mm. Zonally evaporation between Moa’s and Cristal Mountains on highest areas is for about 900 mm [33].

2.2. Sampling Methodology

Coordinate were took in the studied area and a 5 Km radio delimited in wich territory inventories were executed with the exposed characteristic. For studied vegetal formation specific denomination criterion were followed [21, 22]. The vegetation inventories (stants, samples, relevés) were done by using the Braun Blanquet [34] method, following the experience of various authors [26, 31, 35].

For the vertical structure, the distributions of species in layers were considered by Samek [37]. Consider as sublayers when inside a layer exist a group of elements with good defined altitudes and are different in between. In layer and synucia description the following categories for present species were stablished in Reyes & Acosta Cantillo [38]. In addition oecotope observations were made in stants and its surronders; in inventories place inclination of slope, exposition, altitude (masl), general relief and nano and micro relief were measured or estimated. The ordination of vegetation inventories and separation of syntaxa was carrying out by phytocoenological methods [39, 36]. For the association characteristic combinations the used species are those with degree of presence IV and V [39] and for subassociations the differential combinations. The syntaxa denomination was carrying out according to Internacional Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature [40].

In the character species designation of the alliance recommendations of Braun Blanquet [34] were used as: absolutely restricted (fidel, true), strongly associated and favorably associated. In the humus layers stratification was measuring (cm), the existence of roots and rootlets were registered and roots mat characteristics [41]. Completed scientific names (genus, species and author) could be observed in Tables and Acevedo-Rodriguez & Strong [42] sometime amended by other authors [43, 44, 45, 46]. Collected plants determinations were made by herbarium comparison of specimen existing in the Centro Oriental de Ecosistemas y Biodiversidad (Herbarium BSC). Also intrinsic characteristics of communities were studied by using the not parametric indexes Chao2 and Jacknife 1 [47], and so on beta diversity using classic formulations of Jaccard (c / a+b+c x 100) and Sorensen (2c / A+B x 100) founded in Mueller Dombois & Ellemberg [36].

3. RESULTS

Sintaxonomy

In this work one alliance and two associations were descripted, developing at the same time the following phytosociological arrangement:

¾ Class Tabebuio dubiae - Calophylletea utilis Reyes class. nov. In this contribution.

Holotypus: Tabebuio dubiae - Calophylletalia utilis ord. nov. Two rainforests types were found, the low and submontane rainforests on ophiolites (sclerophyll rainforest) and submontane rainforest on bad drainage soils. Canopy layer have about 20 to 25 m tall and 80 to 100 % cover. Rainfall is between 1 500 to 3 500 mm, with a regular distribution. Rocks are ophiolites and soils are ferritic dark red and ferrític yellowish leach. They are present since Nipe`s plateau (20033ʹNorth, 75047ʹWest – west locality) until Miel’s river basin (20013ʹNorth, 74031ʹWest – east locality).

Composition & character species. Strongly associated: Calophyllum utile, Tabebuia dubia, Sloanea curatellifolia, Alsophylla minor, Terminalia aroldoi (T. nipensis), Coccoloba wrightii, Cyrilla coriacea, Buxus rotundifolia, Pimenta odiolens, Podocarpus ekmanii, Bonnetia cubensis, Ravenia ekmanii, Protium fragans, Byrsonima biflora (B. cuneata), Antirhea shaferi, Laplacea moensis, Lyonia lippoldii, Calycogonium grisebachii, Euphorbia munizii, Votomita monantha, Spathelia wrightii, Miconia jashaferi, Miconia moensis, favorably associated: Byrsonima spicata, Hieronyma nipensis, Magnolia cubensis ssp. cubensis, Guapira rufescens, Guatteria blainii, Sideroxylon jubilla, Matayba domingensis, Coccoloba shaferi, Guettarda valenzuelana.

¾ Order Tabebuio dubiae-Calophylletalia utilis Reyes ord. nov.

Holotypus: Pimento odiolentis-Calophyllion utilis Reyes 2017. With the characteristics of the class. Sintaxonomy. When Tabebuio dubiae - Calophylletea utilis class nova is compared with Ocoteo - Cyrilletea racemiflorae Borhidi 1996 it has a 90,7 and 88,5 % respectively of difference between their characteristics combinationʹs species. At the same time when confront the new order Tabebuio dubiae - Calophylletalia utilis with Podocarpo ekmanii - Sloanetalia curatellifoliae Borhidi and Muñiz 1996 they had a 75 and 67 % respectively of dissimilarity. I transfer in this paper Pimento odiolentis-Calophyllion utilis Reyes 2017 from Borhidiʹs class and order to Tabebuio dubiae - Calophylletea utilis Reyes.

Studied alliance: Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuion dubiae Reyes.

¾ Alliance Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuion dubiae Reyes all. nov. In this contribution.

Holotypus: Terminalio aroldoi-Tabebuietum dubiae Reyes & Acosta ass. nov. Composition & character species. Strongly associated: Terminalia aroldoi (Terminalia orientensis), Chaetocarpus globosus subsp oblongatus, Coccoloba wrightii, C. diversifolia, Calycogonium grisebachii, Callicarpa oblanceolata; favorably associated: Tabebuia dubia, Macrocarpae pinetorum, Mazaea shaferi, Varronia nipensis and Cyrilla coriacea. Vegetal formation is submountain rainforest on ophiolites. The canopy layer has about 20 m high with 80 to 90 % cover. Rocks are ultramafics and soils are ferritic dark red, from shallow to moderately deep, good drainage and fresh. In the general sense the edafotope is poor and acidic. Rainfalls vary in about 2 000 mm and temperature average is 210C. This alliance is limited to Sierra del Cristal, it was study between 680 and 840 m above sea level. When Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuion dubiae is compared with Pimento odiolentis - Calophyllion utilis Reyes 2017 it has a 80 and 90 % of difference between their species, and with Podocarpo ekmanii-Byrsonimion orientensis Borhidi & Muñiz 1996 of 94 to 80 % of dissimilarity.

Found association: Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuietum dubiae Reyes & Acosta.

¾ Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuietum dubiae Reyes & Acosta ass. nov. In this contribution.

Holotypus: Table 1, rel. 8. Vegetal formation is submountain rainforest on ophiolites. The canopy layer shows a discontinuity (continental), with trees heigth between seven and 20 m and a cover of 80 to 90 %. The constant and abundant species are Tabebuia dubia (Wr. ex Sauv.) Britt. ex Seibert., Calophyllum utile Bisse, Cyrilla coriacea Berazaín and Podocarpus ekmanii Urb.; also constant are Sideroxylon jubilla (Ekm. ex Urb.) Gaertn. and Hieronyma nipensis Urb. and as frequent Pera sp. (abundant sometimes), the rest of species are found in Table 1.

Shrub layer is relatively dense, with a variable cover between 50 and 90 %, constant and abundant species are Miconia baracoensis Urb. and Cyathea parvula (Jenm.) Domin; while Coccoloba wrightii Lindau is constant. Herbaceous layer cover is between 40 and 95 %, but frequently between 50 and 90 %. Constant species are Tabernaemontana amblyocarpa Urb., Callicarpa oblanceolata Urb., Cyathea parvula (abundant), Piper sp., Bactris cubensis Burret and Antirhea shaferi Urb., etc (Table 1). Between lianas constant are Platygyna hexandra (Jacq.) Muell. Arg. and Mikania hioramii Britton & B. L. Rob. and as frequent Smilax havanensis Jacq. and Vanilla bicolor Lindl. As epiphytal synucia Guzmania monostachia (L.) Rusby ex Mez (abundant) and Elaphoglossum chartaceum (Bak. ex Jenm.) C. Christ. are constants Marcgravia evenia Krug & Urb. subsp. and evenia as frequent. Species which contribute 75 % or more of fallen leaves are Calophyllum utile, Tabebuia dubia, Matayba oppositifolia (A. Rich.) Britton, Cyrilla coriacea, Clusia tetrastigma Vesque and locally Sideroxylon jubilla, Hieronyma nipensis, Guettarda monocarpa Urb. and Miconia baracoensis. Commonly in this phytocoenosis is found a big quantity of fallen and rotten trees which generally are covered by lichens and moss.

It developed in Sierra del Cristal and was studied between June 18 to 23 2000 (20032′North, 75042′West and 20032′North, 75028′West), mainly in the south slope, between 680 and 840 m above sea level, the conservation is good. Rainfall level is about 2 000 mm and average of temperature is nearly 200C. The presence of fog and low clouth in this area is important for the preponderant economy of water in this ecosystem. Soils are red ferritic poor and acidic over ophiolite complex rocks, sometimes rocky outcrops are found in surface. The humus layers are well developed; L layer is uniform distributed in surface with a 5 to 10 cm variation. Layers F and H generally are mixed and constituted a root mat between 8 and 15 cm, more frequently between 10 and 15 cm.

Characteristic combination reach 36 species (see Table 1). Two subassociations are present:

¾ Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuietum dubiae tabernaemontanetosum ambliocarpae Reyes subass. nov.

¾ Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuietum dubiae typicum Reyes subass. nov.

Differences in between depend of soil deep. The subassociation tabernaemontanetosum ambliocarpae (Typus: Table 1, rel. 4) developed over shallow soils and generally with rocky outcrops in surface (differential combination can be observed in Table 1). While typicum subassociation (Typus: Table 1, rel. 8) present in moderately deep soils with no surface rocky outcrops, and is characterized mainly for absence of species that compound differential combination of the other subassociation, the only positive difference is Magnolia sp. and other species that conform differential combinations of the variants (Table 1).

Two variants are found Eugenia floribunda and Dicranopteris flexuosa. The first is observed in places where environmental moisture is big with a differential combination compound by Eugenia floribunda (Willd.) O. Berg, Homolepis glutinosa (Sw.) Zuloaga & Soderstr. and Tolumnia sp. Second is present in the greater heigh of the association and is defined by Machaerina filifolia Griseb., Dicranopteris flexuosa (Schrad.) Underw. and Byrsonima sp. and are absent Jacaranda arborea Urb., Platygyna hexandra e Ilex nitida (Vahl) Maxim. that are part of characteristic combination.

Table 1. Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuietum dubiae in the ophiolitic rainforests of Sierra del Cristal. Pp- shallow, Mp- moderate deep, SW – southwest, NE – northeast, SE – southeast, S – south.

|

Subassociations |

Tabernaemontanetosum ambliocarpae |

Typicum |

Presen |

||||||||||

|

Variants |

|

|

|

|

|

Eugenia floribunda |

Dicranopteris flexuosa |

|

|||||

|

N. order. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

||

|

Altitude (masl) |

755 |

680 |

780 |

760 |

770 |

770 |

780 |

780 |

840 |

830 |

|

||

|

Inclination (degrees) |

20 |

35 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

12 |

15 |

10 |

15 |

10 |

|

||

|

Exposition |

SW |

NE |

SE |

SW |

SE |

NE |

SE |

SE |

S |

SE |

|

||

|

Soils |

Pp |

Pp |

Pp |

Pp |

Pp |

Mp |

Mp |

Mp |

Mp |

Mp |

|

||

|

E3 - Canopy layer (covers %) |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

90 |

90 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

|

||

|

E2 - Shrub layer (%) |

50 |

90 |

90 |

70 |

60 |

80 |

80 |

70 |

50 |

60 |

|

||

|

E1 - Herbaceous layer (%) |

95 |

90 |

50 |

50 |

40 |

50 |

40 |

70 |

90 |

50 |

|

||

|

N. species |

51 |

57 |

47 |

52 |

50 |

50 |

43 |

54 |

53 |

44 |

50.1 |

||

|

Characteristics |

|||||||||||||

|

E3,1 - Tabebuia dubia (Wr. ex Sauv.) Britt. ex Seibert. |

4.2 |

4.2 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

2.1 |

4.1 |

3.1 |

V(2-4) |

||

|

Calophyllum utile Bisse |

2.1 |

2.1 |

4.2 |

3.1 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

3.1 |

4.2 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

V(1-4) |

||

|

Podocarpus ekmanii Urb. |

3.1 |

3.1 |

2.1 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

1.1 |

. |

2.1 |

+.1 |

2.1 |

V(+-3) |

||

|

Cyrilla coriacea Berazaín |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

3.2 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

V(1-3) |

||

|

Matayba oppositifolia (A. Rich.) Britt. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

3.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

2.1 |

3.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

V(r-3) |

||

|

Hieronyma nipensis Urb. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

3.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

V(r-3) |

||

|

Sideroxylon jubilla (Ekm. ex Urb.) Gaertn. |

2.1 |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

V(r-2) |

||

|

E2,1 - Cyathea parvula (Jenm.) Domin |

2.1 |

1.1 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

2.1 |

r.1 |

2.1 |

3.2 |

1.1 |

V(r-3) |

||

|

Miconia baracoensis Urb. |

+.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

V(r-2) |

||

|

Chaetocarpus globosus subsp. oblongatus (Alain) Borhidi |

r.1 |

3.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

V(r-3) |

||

|

Bactris cubensis Burret |

+.1 |

+.1 |

1.2 |

r.1 |

1.2 |

r.1 |

+.1 |

1.2 |

. |

r.1 |

V(r-1) |

||

|

E2 - Ditta myricoides Griseb. |

2.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

V(r-2) |

||

|

Clusia tetrastigma Vesque |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

2.2 |

r.1 |

2.1 |

3.2 |

V(r-3) |

||

|

Coccoloba wrightii Lindau |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

V(r-1) |

||

|

Guapira obtusata (Jacq.) Britt. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

V(r-1) |

||

|

E1 - Callicarpa oblanceolata Urb. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

V(r) |

||

|

Piper sp. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

V(r) |

||

|

Ep- Guzmania monostachia (L.) Rusby ex Mez |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

2.2 |

V(1-2) |

||

|

E3,2 - Pera sp. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

IV(r-2) |

||

|

E3,1 - Zanthoxylum cubense P. Wils. |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

IV(r-1) |

||

|

Terminalia aroldoi Bisse (Terminalia orientensis Monach.) |

r.1 |

2.1 |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

IV(r-2) |

||

|

Chionanthus domingensis Lam. |

. |

2.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

IV(r-2) |

||

|

Jacaranda arborea Urb. |

1.1 |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

IV(r-1) |

||

|

Guatteria blainii (Griseb.) Urb. |

1.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

r.1 |

. |

IV(r-1) |

||

|

E2,1 - Mazaea shaferi (Standl.) Delprete |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

. |

1.1 |

IV(1-2) |

||

|

Calycogonium grisebachii Triana |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

IV(r-2) |

||

|

Guettarda monocarpa Griseb. |

2.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

. |

2.1 |

. |

. |

1.1 |

IV(r-2) |

||

|

Laplacea sp. |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

IV(r-1) |

||

|

Ilex nitida (Vahl) Maxim. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

IV(r-1) |

||

|

Coccoloba diversifolia Jacq. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

+.1 |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

IV(r-1) |

||

|

E1 - Anthirea shaferi Urb. |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

+.1 |

2.1 |

+.1 |

2.1 |

IV(r-2) |

||

|

Ilex sp. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

IV(r-1) |

||

|

L- Marcgravia evenia Krug & Urb. subsp. evenia |

+.1 |

+.1 |

. |

r.1 |

. |

+.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

IV(r-+) |

||

|

Smilax havanensis Jacq. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

IV(r) |

||

|

Vanilla bicolor Lindl. |

+.1 |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

IV(r-+) |

||

|

Platygyna hexandra (Jacq.) Muell. Arg. |

r.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

IV(r-+) |

||

|

Ep- Elaphoglossum chartaceum (Bak. ex Jenm.) C. Christ. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.2 |

r.1 |

r.2 |

r.2 |

1.2 |

r.1 |

1.2 |

IV(r-1) |

||

|

Differentials |

Tabernaemontanetosum ambliocarpae |

Typicum |

|

||||||||||

|

E2 - Tabernaemontana ambliocarpa Urb. |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

III(r-1) |

||

|

E1 - Neobracea valenzuelana (A. Rich.) Urb. |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

III(r-1) |

||

|

Arthrostylidium sp. |

4.3 |

4.3 |

2.2 |

1.2 |

+.2 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

III(+-4) |

||

|

Coccocypselum herbaceum Aubl. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

III(r-+) |

||

|

E3 - Magnolia sp. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

III(r-1) |

||

|

E2,1 - Eugenia floribunda West. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

2.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

II(r-2) |

||

|

E1 - Homolepis glutinosa (Sw.) Zuloaga & Soderstr. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.2 |

r.2 |

r.2 |

. |

. |

II(r) |

||

|

Tolumnia sp. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

II(r-+) |

||

|

E2 - Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Kunth |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

II(r-1) |

||

|

E1 - Machaerina filifolia Griseb. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1.2 |

. |

. |

. |

2.2 |

2.2 |

II(1-2) |

||

|

Dicranopteris flexuosa (Shrod.) Underw. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.2 |

r.2 |

I(r) |

||

|

Accompaniers |

|||||||||||||

|

E1 - Palicourea alpina (Sw.) DC. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

3.2 |

. |

3.2 |

III(r-3) |

||

|

Varronia nipensis (Urb.) Borh. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

III(r) |

||

|

Mikania hioramii Britton & B. L. Rob. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

III(r) |

||

|

Hedyosmum nutans Sw. |

. |

r.1 |

+.1 |

. |

. |

2.2 |

r.1 |

1.1 |

3.2 |

. |

III(r-3) |

||

|

Scleria secans (L.) Urb. |

. |

. |

+.2 |

+.2 |

+.2 |

. |

. |

+.2 |

r.2 |

. |

III(r-+) |

||

|

Ep- Epidendrum nocturnum Jacq. |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

III(r) |

||

|

E3 - Pinus cubensis Griseb. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

II(r) |

||

|

Lyonia sp. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

II(r) |

||

|

E2,1 - Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R. Br. ex Roem |

r.1 |

+.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

II(r-+) |

||

|

Erithalis sp. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

II(r) |

||

|

E1 - Miconia dodecandra (Desv.) Cogn. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

2.1 |

. |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

II(r-2) |

||

|

Ilex macfadyenii (Walp.) Rehder subsp. macfadyenii |

. |

+.1 |

1.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

II(r-1) |

||

|

Casearia crassinervis Urb. |

. |

. |

+.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

. |

II(r-1) |

||

|

L- Lygodium volubile Sw. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

II(r) |

||

|

Ep- Dilomilis oligophylla (Schltr.) Summerhayes |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

II(r) |

||

|

Dichaea hystricina Rchb. f. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

II(r) |

||

|

E1 - Ichnanthus mayarensis (Wr.) Hitchc. |

. |

. |

+.2 |

+.2 |

+.2 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II(+) |

||

|

Lepidaploa wrightii (Sch. Bip.) H. Rob. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

II(r-+) |

||

|

Macrocarpae pinetorum Alain |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+.1 |

. |

. |

II(r-+) |

||

|

Scleria sp. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

+.2 |

r.2 |

. |

+.2 |

. |

. |

II(r-+) |

||

|

L- Chiococca alba (L.) Hitchc. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II(r) |

||

|

Ipomoea carolina L. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

II(r) |

||

|

E3,2 - Clusia rosea Jacq. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I(r) |

||

|

E3,1 - Sloanea curatellifolia Griseb. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I(r) |

||

|

Schefflera morototoni (Aubl.) Maguire |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I(r) |

||

|

E2,1- Coccoloba nipensis Urb. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

I(r) |

||

|

E1- Cupania americana L. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I(r) |

||

|

Pimenta odiolens (Urb.) Burret |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

I(r) |

||

|

Koanophyllon rhexioides (B.L. Robins.) King & Robins. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

I(r) |

||

|

Clerodendrum sp. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

I(r) |

||

|

L- Passiflora sexflora A. Juss. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I(r) |

||

|

Ep- Trichomanes scandens L. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.2 |

r.2 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

I(r) |

||

|

Jacquiniela globosa (Jacq.) Schltr. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

. |

I(r) |

||

In addition. Inv. 1. Tabebuia sp. r.1, Pteridium caudatum (L.) Maxon r.2, Tillandsia sp. +.1, T. bulbosa Hook. r.1, Erythrodes sp. r.1; Inv. 2. Ocotea leucoxylon (Sw.) Mez r.1, Ficus membranacea C. Wr. r.1, Pimenta racemosa (Mill.) J.W. Moore r.1, Buchenavia tetraphylla (Aubl.) R.A. Howard 1.1, Gesneria sp. r.1, Phaius tankervilliae (Banks) Blume r.1, Spathelia sp. r.1, Blechnum occidentale L. +.2, Passiflora penduliflora Bert. r.1, Echites umbellata Jacq. r.1, Peperomia maculosa (L.) Hook. +.1, Philodendron lacerum (Jacq.) Schott r.1, Nephrolepis rivularis (Vahl) Mett. ex Krub +.2; Inv. 3. Tillandsia fasciculata Sw. r.1; Inv. 4. Coccothrinax orientalis (León) O. Muñiz & Borhidi r.1, Vernonia sp. r.1, Oeceoclades maculata (Ldl.) Ldl. r.2, Tillandsia pruinosa Sw. r.1; Inv. 6. Casearia sylvestris Sw. var. sylvestris r.1, Elaphoglossum herminieri (Bory & Fee) T. Moore r.2, Hymenophyllum polyanthos (Sw.) Sw. r.2, Inv. 7. Lyonia macrophylla (Britt.) Ekm. ex Urb. r.1; Inv. 9. Smilax lanceolata L. r.1, Koanophyllon polystictum (Urb.) King & Robins. r.1, Macrocarpae pinetorum Alain r.1, Sticherus remotus (Kaulf.) Spreng. 2.2, Galactia sp. r.1; Inv. 10. Erythroxylum sp. r.1, Adiantopsis paupercula (Kuntze) Fée r.2.

¾ Pimento odiolentis - Calophyllion utilis Reyes 2017

Found association: Buxo rotundifoliae-Calophylletum utilis ass. nov.

¾ Buxo rotundifoliae-Calophylletum utilis Reyes & Acosta ass. nov. In this contribution.

Holotypus: Table 2, rel. 2. This submountain rainforest on ophiolites was intensely exploted, although it’s locally structure and floristic composition is conserved, choosing for the relevés the more conserved areas. The arboreal layer is between 10 and 20 m high, occasionaly are observed predominants even 25 m and cover between 70 and 90 %. In this layer constant and abundant species are Calophyllum utile, Jacaranda arborea, Bactris cubensis, Tabebuia dubia, Hieronyma nipensis and Antirhea shaferi, abundant in occasions Sideroxylon jubilla and Matayba oppositifolia (Table 2).

Shrub layer is relatively dense with a cover between 40 and 80 %. Abundant species are Cyathea parvula, Spathelia vernicosa Planch., Palicourea crocea (Sw.) Roem. & Schult., Buxus rotundifolia (Britton) Mathou and Antirhea shaferi. Herbaceous layer is generally very dense, with a cover of 80 to 90 %. The abundant species are Cyathea parvula, Buxus rotundifolia, Arthrostylidium urbanii Pilg. and Miconia moensis (Britton) Alain. Frequently a moss layer is observed with Leucobrium giganteum Mull. reaching occasionally a high cover. In liana synucia more abundant is Platygyna hexandra, that make difficult the field work in this formation, also are frequent although diffuse Vanilla bicolor, Dioscorea nipensis R.A. Howard, Mikania hioramii and Smilax havanensis Jacq. The epiphytic synucia found diffuse and in small quantity, more observed is Guzmania monostachia. Two variants are found Byrsonima biflora and Gesneria nipensis. Both present a clear differential combination observed in Table 2.

In a great part of the area slope is moderate, between five and ten degrees and predominant exposition is north. Soil is ferritic dark red, generally deep. A root mat is observed between 4 and 12.5 cm. It was studied March 15 to 20 2010 in the basin of Revuelta de los Chinos creek (20036′North, 74056′West), south of Moa city and north-northwest of El Toldo, the highest point of Moa’s altitudes.

Table 2. Buxo rotundifoliae - Calophylletum utilis in the ophiolitic rainforests of Alturas de Moa. N – north, E – east.

|

Variants |

Byrsonima biflora |

Gesneria nipensis |

Presen |

||

|

N. order |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

Altitude (masl) |

420 |

350 |

340 |

342 |

|

|

Inclination (degrees) |

15 |

5 |

10 |

10 |

|

|

Exposition |

NNW |

NW |

N |

E |

|

|

E3 - Canopy layer (covers %) |

70 |

90 |

70 |

70 |

|

|

E2 - Shrub layer (%) |

80 |

50 |

40 |

50 |

|

|

E1 - Herbaceous layer (%) |

90 |

80 |

80 |

90 |

|

|

N. species |

64 |

55 |

51 |

53 |

55.7 |

|

Characteristics |

|||||

|

E3,2,1- Calophyllum utile Bisse |

2.1 |

2.1 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

4 (2-3) |

|

Antirhea shaferi Urb. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

4 (1-2) |

|

Zanthoxylum cubense P. Wils. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

4 (r-1) |

|

Clusia tetrastigma Vesque |

r.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

4 (r-1) |

|

Matayba oppositifolia (A. Rich.) Britt. |

+.1 |

r.1 |

3.1 |

2.1 |

4 (r-3) |

|

Bactris cubensis Burret |

+.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

4 (+-2) |

|

Cyathea parvula (Jenm.) Domin |

3.2 |

3.1 |

4.3 |

3.2 |

4 (3-4) |

|

E3,2- Sideroxylon jubilla (Ekm. ex Urb.) Gaertn. |

+.1 |

2.1 |

+.1 |

2.1 |

4 (+-2) |

|

E3,1- Jacaranda arborea Urb. |

2.1 |

3.2 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

4 (1-3) |

|

Ditta myricoides Griseb. |

1.1 |

+.1 |

+.1 |

1.1 |

4 (+-1) |

|

E2,1- Buxus rotundifolia (Britt.) Mathou |

2.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

3.2 |

4 (1-3) |

|

Spathelia pinetorum M. Vict. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

4 (1-2) |

|

Miconia moensis (Britt.) Alain |

2.1 |

1.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

4 (r-2) |

|

Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R. Br. ex Roem |

+.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

+.1 |

4 (r-+) |

|

Palicourea crocea (Sw.) Roem. & Schult. |

3.1 |

2.1 |

3.2 |

1.1 |

4 (1-3) |

|

E1- Piper arboreum Aubl. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

4 (r-1) |

|

Clidemia umbellata (Mill.) L.O. Williams |

r.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

+.1 |

4 (r-+) |

|

E0- Leucobrium giganteum Mull. Hal. |

3.2 |

+.2 |

+.2 |

1.2 |

4 (+-3) |

|

L- Marcgravia evenia Krug. & Urb. subsp. evenia |

r.1 |

+.1 |

+.1 |

1.1 |

4 (r-1) |

|

Arthrostylidium urbanii Pilg. |

3.3 |

3.3 |

2.2 |

3.3 |

4 (2-3) |

|

Platygyna hexandra Jacq. |

2.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

4 (1-2) |

|

E3,2,1- Tabebuia dubia (Wr. ex Sauv.) Britt. ex Seibert. |

1.1 |

3.2 |

1.1 |

. |

3 (1-3) |

|

Hieronyma nipensis Urb. |

1.1 |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

3 (1) |

|

Ilex repanda Loes |

1.1 |

+.1 |

. |

+.1 |

3 (+-1) |

|

E3- Guapira obtusata (Jacq.) Britt. |

+.1 |

. |

2.1 |

+.1 |

3 (+-2) |

|

Byrsonima moensis Acuña & Roig |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

+.1 |

3 (r-1) |

|

Plumeria obtusa L. subsp. obtusa. |

+.1 |

r.1 |

. |

r.1 |

3 (r-+) |

|

E3,2- Ouratea striata (V. Tiegh) Urb. |

1.1 |

+.1 |

. |

r.1 |

3 (r-1) |

|

E3,1- Podocarpus ekmanii Urb. |

1.1 |

+.1 |

1.1 |

. |

3 (+-1) |

|

E2,1- Scolosanthus lucidus.Britt. |

+.1 |

1.1 |

. |

r.1 |

3 (r-1) |

|

Tapura cubensis (Poepp. & Endl.) Griseb. |

+.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

. |

3 (r-+) |

|

Chionanthus domingensis Lam. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

+.1 |

. |

3 (r-+) |

|

Cordia sp. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

3 (r) |

|

L- Vanilla wrightii Rchb. |

r.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

. |

3 (r-+) |

|

Dioscorea grisebachii Planch. |

r.1 |

+.1 |

. |

+.1 |

3 (r-+) |

|

Mikania hioramii Britton & B. L. Rob. |

r.1 |

+.1 |

+.1 |

. |

3 (r-+) |

|

Smilax havanensis Jacq. |

r.1 |

+.1 |

r.1 |

. |

3 (r-+) |

|

Ep- Guzmania monostachia (L.) Rusby ex Mez |

r.1 |

+.1 |

. |

r.1 |

3 (r-+) |

|

Differentials |

Byrsonima biflora |

Gesneria nipensis |

|

||

|

E3,1- Byrsonima biflora Griseb. (Byrsonima cuneata (Turcz.) P. Wilson) |

2.1 |

1.1 |

. |

. |

2 (1-2) |

|

E3- Guatteria cubensis Bisse |

+.1 |

1.1 |

. |

. |

2 (+-1) |

|

Cyrilla coriacea Berazaín |

+.1 |

(r.1) |

. |

. |

2 (r-+) |

|

E2,1- Coccoloba shaferi Britt. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

2 (r) |

|

Chaetocarpus acutifolius (Britton & P. Wilson) Borhidi |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

2 (r) |

|

E1- Vernonanthura hieracioides (Griseb.) H. Rob. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

2 (r) |

|

Ilex macfadyenii (Walp.) Rehder subsp. macfadyenii |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

. |

2 (r) |

|

Ovieda cubensis Schauer) I.E. Mendez (Clerodendron lindenianum A. Rich.) |

r.1 |

+.1 |

. |

. |

2 (r-+) |

|

E3,2,1- Gesneria nipensis Britt. & P. Wils. |

. |

. |

2.1 |

r.1 |

2 (r-2) |

|

E3,1- Sloanea curatellifolia Griseb. |

. |

. |

1.1 |

1.1 |

2 (1) |

|

Schefflera morototoni (Aubl.) Maguire |

. |

. |

+.1 |

r.1 |

2 (r-+) |

|

Ocotea leucoxylon (Sw.) Mez |

. |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

2 (r-1) |

|

Guatteria blainii (Griseb.) Urb. |

. |

. |

1.1 |

r.1 |

2 (r-1) |

|

E2,1- Casearia sylvestris Sw. |

. |

. |

1.1 |

r.1 |

2 (r-1) |

|

Hyperbaena cubensis Urb. |

. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

2(r) |

|

L- Schradera cephalophora Griseb. |

. |

. |

+.1 |

+.1 |

2 (+) |

|

Accompaniers |

|||||

|

E3,2,1- Guapira rufescens (Griseb.) Lund. |

. |

3.1 |

. |

1.1 |

2 (1-3) |

|

Neobracea valenzuelana (A. Rich.) Urb. |

. |

+.1 |

. |

r.1 |

2 (r-+) |

|

E3,1- Clusia rosea Jacq. |

. |

r.1 |

1.1 |

. |

2 (r-1) |

|

Tabernaemontana ambliocarpa Urb. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

+.1 |

2 (r-+) |

|

E2,1- Erythroxylon longipes O.E. Schulz. |

2.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

2 (r-2) |

|

E1- Solanum gundlachii Urb. |

+.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

2 (r-+) |

|

Purdiaea velutina Britt. & Wils. |

r.1 |

. |

1.1 |

. |

2 (r-1) |

|

Alvaradoa arborescens Griseb. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

2 (r) |

|

Coccocypselum herbaceum Aubl. |

. |

r.1 |

r.1 |

. |

2 (r) |

|

Mecranium amygdalinum (Desr.) C. Wright |

. |

+.1 |

r.1 |

. |

2 (r-+) |

|

L- Cissus grisebachii Planch. |

r.1 |

. |

. |

r.1 |

2 (r) |

In addition. Inv. 1. Jacaranda coerulea Griseb. +.1, Lyonia sp. +.1, Illicium cubense A.C. Smith +.1, Magnolia sp. r.1, Pera bumeliifolia Griseb. 1.1, Chaetocarpus globosus subsp. oblongatus (Alain) Borhidi r.1, Rubiaceae +.1, Ossaea sp. 1.1, Eugenia sp. r.1, Vernonia sp. +.1, Casearia sp. r.1, Hedyosmum nutans Sw. +.1, Tillandsia fasciculata Sw. r.1, Aechmea nudicaulis (L.) Griseb. r.1; Inv. 2. Guettarda monocarpa Urb. r.1, Laplacea sp. +.1, Maytenus sp. r.1, Galactia sp. r.1, Phylodendron lacerum (Jacq.) Schott r.1; Inv. 3. Calyptronoma occidentalis (Sw.) H.E. Moore +.1, Miconia dodecandra (Desv.) Cogn. 1.1, Micropolis polita Pierre subsp. polita r.1, Linodendron aroniifolium Griseb. +.1, Guettarda valenzuelana A. Rich. r.1, Oplismenus sp. r.1; Inv. 4. Ocotea cuneata (Griseb.) Urb. 1.1, Coccoloba sp. r.1, Psychotria sp. r.1, Miconia jashaferi Majure & Judd +.1, Meriania albiflora Carmenate & Michelangeli r.1, Ocotea spathulata Mez r.1, Philodendron consanguineum Schott r.1, Triopteris jamaicensis L. var. ovata r.1, Lygodium cubensis Humb., Bonb. & Kanth +.1.

Beta diversity (β)

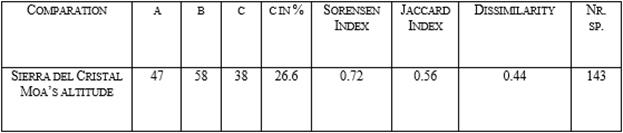

In the floristic comparation between Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuietum dubiae (Sierra del Cristal) and Buxo rotundifoliae-Calophylletum utilis (Moa’s altitude); values contrast (0.44 dissimilarity), at the same time both reach a high common species percentaje (c) (Table 3). When exposed community are studied, in the non parametric indexes Chao2 and Jackknife 1 small differences are observed, in Sierra del Cristal, with 96 species, found values are 122 and 118.5 and in north of Moa’s altitude, with 70, 78.2 and 85.7 respectively.

Table 3. Comparation of Beta diversity (β) between syntaxa of Sierra del Cristal and north part of Moa’s altitude.

4. DISCUSSION

Low and submontane rainforest on ophiolites have their maximum expression at Sierra de Cristal area and Moa’s altitudes. This forest have some characterictics about conservation and nutrients recycling [10] and some kind are similar to amazonic vegetation [1, 3] although they are floral different. When compare the average number of species between the two studied associations in this paper and Pimento odiolentis-Calophylletum utilis [31], is observed that Terminalio aroldoi - Tabebuietum dubiae of Sierra del Cristal has the less average number of species with 50,1, while the biggest is present in the before mentioned [31] with 68,0, showing that in this kind of rainforest in Alturas de Moa and Cuchillas del Toa are floral more rich than Sierra del Cristal. Likewise behavior species number of the characteristic combination and the number of wooded species.

Borhidi [20] had recognized the phytogeographic flora of Sierras de Moa and Toa district (Moaënse) as one of the ancient of Cuban archipielago. At the same time López et al. [48] confirmed that in this territory the major number of endemic taxa has been origined. Equally Reyes & Acosta [26]) confirm that Nipe’s and Moa-Baracoa-Asunción-Sierra del Purial remain to biodiversity disposition at least since half of Superior Cretaceous period and that Sierra del Cristal had ocuppy its actual position Maastrichtian or in the early Paleocene, which could have influences about the floral poverty of their phytocoenoses.

Borhidi [49] explains that due of the toxic elements of serpentinites its flora is very specific and for that is considered that these rainforest are very ancient and keep remain cenologically separated of other kind of surrounded vegetation. The great floral similarity and comparts percentage of species between Sierra del Cristal and the north Moa`s (Table 3) indicate that they have a superior diáspora interchange; this is facilited because of vegetation in intermediate zone between both areas is of broadleaf, closer to the rainforest.

5. CONCLUSION

An alliance and two associations are exposed in a new and not studied areas since the phytocenotic point of view this description, with the structural and ecological conditions exposed can be used in the typology and sustainable use of this vegetal formation. The strongest relationships between both areas suggest conditions that made easy species dispersion although with enough differences even at alliances levels.

6. CITED LITERATURE

[1] Rangel-Ch, J.O. (2008). La Vegetación de la Región Amazónica de Colombia. Aproximación inicial. En: Colombia Diversidad Biótica VII. Vegetación, Palinología y Paleoecología (Rangel-Ch, J.O, Ed.) (pp. 1-53). Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogotá.

[2]) Leigh, R.G. Jr. (1982). Estructura y clima en la pluvisilva tropical. En: Evolución en los Trópicos (pp. 161-175). Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

[3] Jordan, C.F. Ed. (1989). An Amazonian Rain Forest. The Structure and Function of a Nutrient Stressed Ecosystem and the Impact of Slash and Burn Agriculture. Man and Biosphere Series. Vol. 2. 176 pp.

[4] Cano, E., A. Veloz & A. Cano-Ortiz (2014). Rain Forests in Subtropical Mountains of Dominican Republic. American Journal of Plant Sciences, 5: 1459-1466. Falta DOI

[5] Martínez-Quesada, E. (2011-2012). Riqueza de especies y endemismo de las espermatófitas de las pluvisilvas de la Región Oriental de Cuba. Revista Jardín Botánico Nacional, 32-33: 79-109.

[6] Martínez -Quesada, E. & M.C. Fagilde (2015). Las espermatófitas de las pluvisilvas de Cuba Oriental. En: Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez de la Naturaleza y el Hombre (ed.). Pluvisilvas cubanas: tesoro de biodiversidad. (pp. 101-127).

[7] PNUD/GEF. (2016). Cuba, metas nacionales para la diversidad biológica 2016-2020. Proyecto PNUD/GEF “Plan Nacional de Diversidad Biológica para apoyar la implementación del Plan Estratégico del CDB 2011 - 2020 en la República de Cuba”. 31.

[8] Reyes, O.J. & L.M. Figueredo Cardona (2019). La conservación de la fitodiversidad ecosistémica en la Sierra Maestra, Cuba Oriental. Rev. Politécnica, (15)30: 1-14.

[9] Fornaris G.E., O.J. Reyes, & F. Acosta (2000). Características fisionómicas y funcionales de la pluvisilva de baja altitud sobre complejo metamórfico de la zona nororiental de Cuba. Biodiversidad de Cuba Oriental, 4: 44-51. Editorial Academia.

[10] Reyes, O.J. & E. Fornaris (2011). Características funcionales de los bosques tropicales de Cuba Oriental. Polibotánica, 32: 89-105.

[11] Rosabal, D. (2017). Diversidad, patrón de coexistencia y distribución espacial de líquenes. En un bosque lluvioso montano de Cuba Oriental. Editorial Academia Española (Ed.). (147 pp.). Omni Scriptum GmbH & Co. KG. Alemania.

[12] Rosabal, D., Burgaz, A.R. & Reyes, O.J. (2012). Diversidad y distribución vertical de líquenes corticícolas en la pluvisilva montana de la Gran Piedra, Cuba. Botánica Complutensis, 36: 19-30.

[13] Font Salmon, O. (2015). Líquenes corticícolas en las pluvisilvas de Pinares de Mayarí y Sierra Cristal (Holguin). En: Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez de la Naturaleza y el Hombre (ed.). Pluvisilvas cubanas: tesoro de biodiversidad. (pp. 186-194).

[14] Caluff, M.G. & G. Shelton (2015). Helechos y plantas afines (Pteridophyta) de las pluvisilvas de Cuba. En: Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez de la Naturaleza y el Hombre (ed.). Pluvisilvas cubanas: tesoro de biodiversidad. (pp. 130-147).

[15] Mustelier, K. (2015). Hepáticas foliosas presentes en los bosques pluviales de Cuba. En: Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez de la Naturaleza y el Hombre (ed.). Pluvisilvas cubanas: tesoro de biodiversidad. (pp. 157-167).

[16] Motito A. & M.E. Potrony (2015). Caracterización de la flora de musgos de los bosques pluviales del oriente cubano. En: Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez de la Naturaleza y el Hombre (ed.). Pluvisilvas cubanas: tesoro de biodiversidad. (pp. 169-180).

[17] Almarales Castro, A. & L. del Castillo (2015). Consideraciones acerca de algunos hongos macroscópicos de Viento Frío, reserva de la biosfera Cuchillas del Toa. En: Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez de la Naturaleza y el Hombre (ed.). Pluvisilvas cubanas: tesoro de biodiversidad. (pp. 181-186).

[18] Martinez-Quesada, E. (2006). Caracterización florística, morfológica y fitogeográfica de las pluvisilvas de la región oriental cubana, mediante espermatofitas. (Tesis Master en Botánica, Mención Sistemática en Plantas Superiores. Jardín Botánico Nacional). Universidad de la Habana.

[19] Martínez Quesada, E., M.C. Fagilde, W.S. Alverson, C. Vriesendorp & R.B. Foster (2005). Seed plants (Spermatophyta). En: Rapid Biological Inventories 14. Maceira, D., A. Fong, W.S. Alverson & T. Wachter (Eds.). (pp. 182–184). The Field Museum, Chicago, IIIn.

[20] Borhidi A. (1996). Phytogeography and Vegetation Ecology of Cuba. 2 Ed. Akadémiai Kiadó. Budapest.

[21] Reyes O.J. (2011-2012a). Clasificación de la vegetación de la Región Oriental de Cuba. Revista Jardín Botánico Nacional, 32-33: 59-71.

[22] Reyes O.J. & Acosta Cantillo F. (2005). Vegetación. Cuba: Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt. En: Rapid Biological Inventories 14. Maceira, D., A. Fong, W.S. Alverson & T. Wachter (Eds.). (pp. 54–69). The Field Museum, Chicago, IIIn. 2005.

[23] Reyes, O.J. & Acosta Cantillo, F. (2006). Vegetación. Pico Mogote. En Rapid Biological Inventories. Report 09. Maceira, D., A. Fong & W.S. Alverson (Eds.). (pp. 40-46). The Field Museum, Chicago, IIIn.

[24] Reyes O.J. (2005). Estudio sinecológico de las pluvisilvas submontanas sobre rocas del complejo metamórfico. Foresta Veracruzana, 7(2): 15-22.

[25] Reyes, O.J. (2016). Forest typology of broadleaf forests from Sierra Maestra, Eastern Cuba. Lazaroa, 37: 1-61.

[26] Reyes O.J. & Acosta Cantillo F. (2018). Fitocenosis en la pluvisilva de baja altitud sobre rocas metamórficas, Cuba Oriental. Revista del Jardín Botánico Nacional, 39: 49-57.

[27] Núñez Jiménez A. & Viña Bayés N. (1989). Regiones Naturales Antró,picas. En Nuevo Atlas Nacional de Cuba. Inst. Geografía e ICGC (eds.). (pp. XII.2.1).

[28] Reyes, O.J. (2011-2012b). Zonas emergidas de Cuba Oriental, su influencia sobre la flora cubana. Revista del Jardín Botánico Nacional, 32-33: 73-78.

[29] Reyes O.J. (2000). Las cuencas de los ríos Toa y Duaba como parte de la región Moa-Baracoa; su importancia en el desarrollo de la flora cubana. Biodiversidad de Cuba Oriental Nr. 5: 50-57.

[30] Guevara, V., Rodríguez Y. & Roque A. (Redactores Temáticos). (2019). Precipitación media hiperanual 1961-2000. En Atlas Nacional de Cuba Nacional de Cuba LX Aniversario.

[31] Reyes O.J. & Acosta Cantillo F. (2017). Fitocenosis en las pluvisilvas sobre ofiolitas del Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt, Cuba Oriental. Caldasia, 3(1): 91-123.

[32] Lapinel B. (1989). Temperatura media anual del aire. En: Nuevo Atlas Nacional de Cuba. Mapa 17. (pp. VI.2.4).

[33] Montenegro U. (1991). Condiciones climáticas de las cuencas de los ríos Toa y Duaba de la provincia de Guantánamo. Inst. Meteorología, ACC, Sgo. de Cuba.

[34] Braun Blanquet J. (1951). Pflanzensoziologie; Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde. 2 Aufl. Wien.

[35] Galán de Mera A. & Vicente Orellana J.A. (2006). Aproximación al esquema sintaxonómico de la vegetación de la región del Caribe y América del Sur. Anales de Biología, 28: 3-27.

[36] Mueller Dombois D. & Ellemberg H. (1974). Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology. John Wiley & Sons Ed.

[37] Samek V. (1973). Pinares de la Sierra de Nipe; Estudio Sinecológico. Acad. Cienc. Cuba, Serie Forestal 14. La Habana.

[38] Reyes O.J. & Acosta Cantillo F. (2011). Fitocenosis en los bosques siempreverdes de Cuba Oriental. III. Pruno-Guareetum guidoniae en la Sierra Maestra. Foresta Veracruzana, 13(1): 1-6.

[39] Scamoni A. & Passarge H. (1963). Einführung in die praktische Vegetationskunde. 2 Aufl. Jena.

[40] Weber H.E., Moravec J. & Theurillat J.P. (2000). International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature. 3rd Edition. Journal of Vegetation Science, 11: 739-768.

[41] Herrera R.A. & Rodríguez M.E. Clasificación funcional de los bosques tropicales. En Herrera R.A., Menéndez L., Rodríguez M.A. & García E.E. (eds). Ecología de los bosques siempreverdes de la Sierra del Rosario, Cuba. (pp. 574-626.). Montevideo. ROSTLAC.

[42] Acevedo-Rodriguez P. & Strong M.T. (2012). Catalogue of Seed Plants of the West Indies. Smithsonian Contributions to Botany 98. 1192 pp.

[43] Greuter W. & Rankin Rodríguez R. (2016). The Spermatophyta of Cuba. A Preliminary Checklist. Part II: Checklist. Botanischer Garten & Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem & Jardín Botánico Nacional, Universidad de La Habana. 398 pp.

[44] Greuter W. & Rankin Rodríguez R. (2017). Vascular plants of Cuba. A preliminary checklist. Second, updated Edition of The Spermatophyte of Cuba, with Pteridophyte added. Botanischer Garten - Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem & Jardín Botánico Nacional, Universidad de la Habana. 444 pp.

[45] Borhidi A., Fernández-Zequeira M. & Oviedo Prieto R. (2017). Rubiáceas de Cuba. Akademiai Kiadó. Budapest.

[46] Sánchez C. (2017). Lista de los helechos y licófitos de Cuba. Brittonia, DOI 10.1007/s12228-017-9485-1. ISSN: 0007-196X (print) ISSN: 1938-436X. (23 June 2017).

[47] Moreno C.E. (2001). Métodos para medir la biodiversidad. Manuales y Tesis SEA. Vol. 1. CYTED. Zaragoza.

[48] López A., Rodríguez M. & Cárdenas A. (1994). El endemismo vegetal en Moa-Baracoa (Cuba Oriental). Fontqueria, 39: 433-473.

[49] Borhidi A. (1999). The Serpentine Flora and Vegetation of Cuba. En The Vegetation of Ultramafic (Serpentine) Soils. (pp. 83–95). Andover, Hampshire, SP 10, UK.